If you work at a tech company, you’ll likely encounter many situations where you need to be able to read and understand a patent.

Whether you need to study another company’s patents to understand the competitive landscape, or analyze one of your own company’s patents to evaluate options, the ability to navigate a patent can be an invaluable skill. It can be useful for innovators and engineers working in research and development, as well as business executives and in-house legal professionals, and everyone in between.

Patents are complex legal documents, so be sure to get a patent attorney involved if you want to do an in-depth analysis of the legal issues and risks at stake. But having a basic understanding of how patents work can help you to make quicker decisions and communicate more effectively with your patent counsel.

With that in mind, we’ve put together this quick guide to walk you through the anatomy of a typical U.S. utility patent.

Information Contained Within a Patent

Broadly, the typical patent consists of four main parts:

- Front page(s)

- Drawings

- Specification

- A background section

- A list of drawings

- A detailed description

- Claims

The specification may also include the following other sections, though these are generally not required:

- A summary section

- A cross-reference to related applications

- A statement of government support

What a Patent Won’t Tell You

However, keep in mind that there are several important things that the patent will not tell you, such as:

- Have the maintenance fees been paid?

- Has the patent expired?

- Who is the current owner of the patent?

- Has the patent been invalidated, enforced, licensed, or sold?

- Have any further applications (like continuations or divisionals) been filed for this subject matter after this patent was granted?

With that overview in mind, let’s take a closer look at each section of a patent application, using an expired patent as an example for reference.

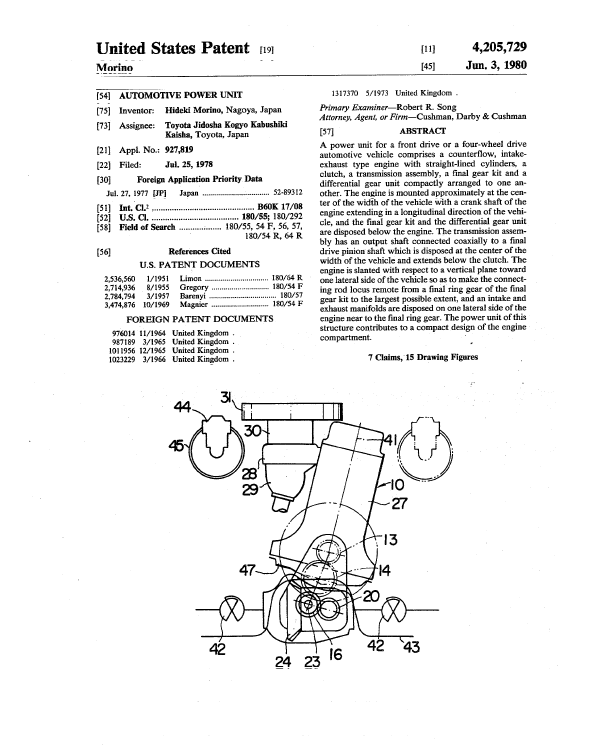

1. Front Page(s)

The Title, Abstract, and Drawings provided on the front page simply summarize the technology described in the patent and the general field of the patent. They’re not the primary sources for determining what the patent actually covers (that’s laid out in the Claims at the end of the patent).

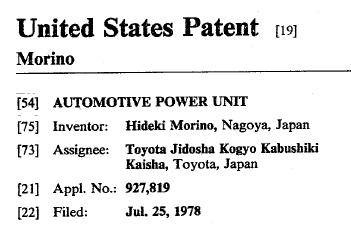

Title

This is fairly self-explanatory — it’s the title of the patent. The patent applicant usually chooses the title, but sometimes the patent office suggests changes during the examination process.

Inventor(s)

The inventors who contributed to the invention claimed in the patent will be listed here, along with their city of residence.

Under U.S. law, patent rights are owned by the inventor(s) by default (i.e., in the absence of an agreement otherwise). So if you want to know who owns a patent, you can start with the inventors. But in the vast majority of cases, the inventors assign their rights to their employer or another business entity.

Assignee

This shows whether the patent was owned by a person or business entity other than the inventors at the time the patent was issued by the U.S. patent office.

But the patent may have been assigned or transferred since it was initially issued. To obtain the most up-to-date public information on the patent’s assignee, check the USPTO assignment database.

Filed (Filing Date)

This is the date when the patent application was filed. But be careful because one or more of the claims in the patent might have an earlier “effective filing date”. The “effective filing date” is important because it’s the watershed date for determining what prior art can be used to invalidate the patent.

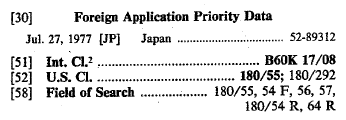

PRIORITY INFORMATION

Sometimes a patent application “claims priority” to one or more earlier patent applications. The earlier patent application is generally referred to as the “priority application.”

Examples of potential “priority applications” include:

- A provisional application

- A foreign application

- A PCT application

- An earlier non-provisional application filed in the United States

Consequently, this section tells you the earlier dates that could be considered the “effective filing date” of the patent. However, a patent will sometimes list a priority application that does not sufficiently describe the claimed invention. Claims that are not sufficiently described in a priority application do not benefit from the priority application’s effective filing date. In these cases, the claims’ effective filing date would default to the “filing date” listed above.

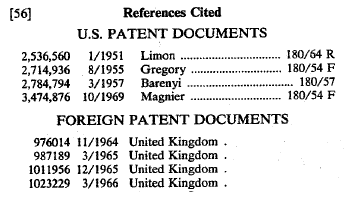

References Cited: Prior Art

This is a list of references that were considered by the patent office during the examination process. In other words, the examiner concluded that the patent’s claims were patentable over the prior art described in these references.

It will be very hard for a third party to use any of the references listed in this section to challenge the validity of the patent (for example, in an IPR proceeding) because it’s presumed that the patent office did its job correctly when initially examining the patent.

Consequently, as a patent owner, you want the closest prior art to be cited here so that you have the strongest presumption of validity in your favor.

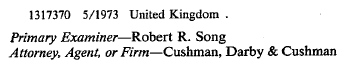

Abstract

This, too, is fairly self-explanatory — this is a brief summary of the invention in broad terms. The Abstract has to be 150 words or less, and it’s often drafted based on the claims that were initially filed in the application that led to the issued patent.

Many people make the mistake of giving too much weight to the abstract because it appears on the front page of the patent. But don’t be deceived — the Claims at the end of the patent (not the Abstract) tell you what is actually covered by the patent, and sometimes the Claims can deviate quite significantly from what’s described in the Abstract.

Representative Drawing

The front page of the patent also includes one representative drawing of the invention at the bottom. Fun fact – the drawing that goes on the front page is selected by the patent examiner (not the inventor) at the end of the examination process. This often defaults to Figure 1, but any drawing could be selected.

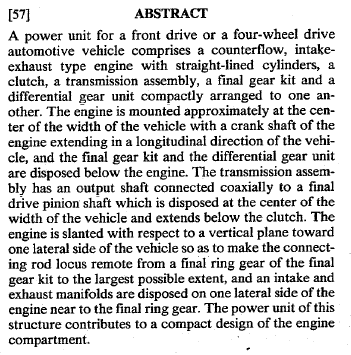

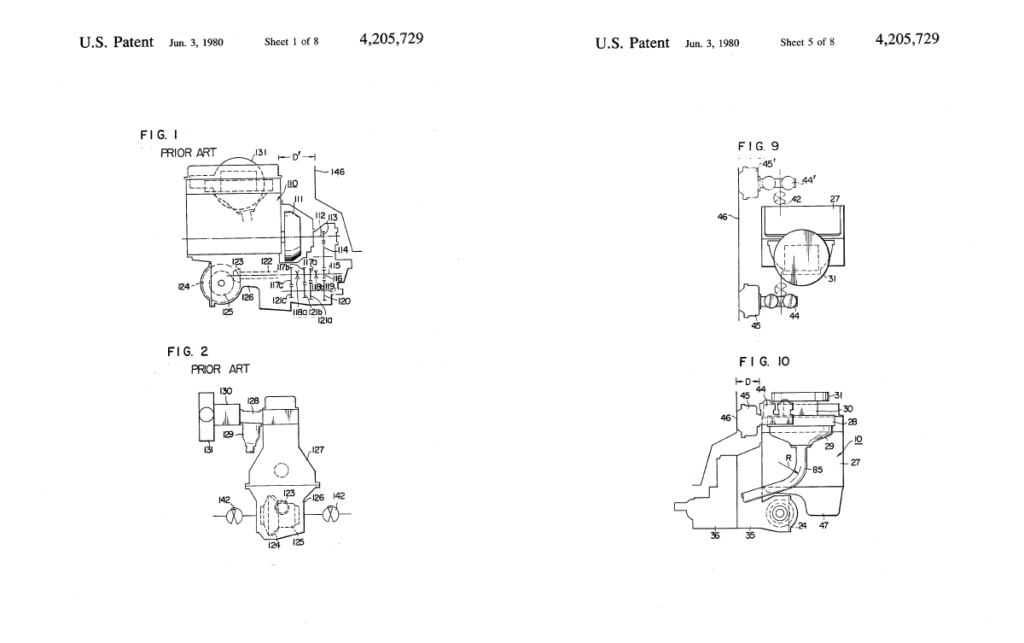

2. Drawings

With a few rare exceptions (for example, if the invention relates to a chemical compound or composition), most U.S. patents will include drawings.

Located immediately following the front page, the drawings help the reader to understand the invention. The drawings must show all claimed elements.

Drawings labeled “Prior Art,” such as Figures 1 and 2 in the example above, are not part of the patented invention. But they’re used to document any prior processes that existed before the invention was made.

3. Specification

Generally, the specification refers to the written part of the patent, not including the front page and the drawings. (Under U.S. law, the claims are technically part of the specification, but we treat them separately in this post because of their importance.)

The specification provides the most relevant context for interpreting the claims in the final section of the patent. For example, if the specification includes a definition for a term in the claims, then the claims will be interpreted using that definition.

Basically, all terminology in the claims will be interpreted in a way that is consistent with the terminology used in the specification. As patent lawyers like to say, “the patentee is their own lexicographer.”

Background

The background briefly describes the general context of the invention. Everything in the background section can potentially be considered “applicant admitted prior art” by the examiner, so the background section often says very little about the actual invention that’s being patented.

Detailed Description

The detailed description (together with the summary section, in some cases) are the main technical disclosure of the patent.

This section lays out the enabling disclosure of the invention — that is, it describes the invention in terms that would allow a person with ordinary skill in the field to be able to make or use the invention. The detailed description also describes the best mode for making and using the inventions.

Each figure and each reference number from the drawings should be called out and named here. The description may also include different embodiments of the invention.

Before we move on to the claims, keep in mind that the entire issued patent can be used as prior art against later-filed patent applications. Basically, if you’re looking at a patent to determine whether your own invention is patentable, the most relevant section for your analysis will typically be the patent’s detailed description.

4. Claims

The most important part of the patent is the claims; the claims set forth and define the patent’s scope of exclusive rights. In other words, they describe what the patent does or does not cover. Each claim element should be shown in the drawings and described in the detailed description.

There are two different ways to categorize the types of claims you’ll find in a typical patent.

System vs. Method Claims

Most patents will include both system and method claims.

System claims generally describe tangible things. It can either be phrased using a broad category (e.g., “system,” “device,” or “apparatus”), or with a narrower term of art (e.g., “drill bit” or “keyboard”). A system claim might use functional language to describe certain elements, but the “elements” of a system claim are components of the system.

Method claims generally describe a process or series of steps. Method claims often refer to a thing that performs the process, but the “elements” of the method claim are the operations themselves. Usually, the steps or operations are styled as gerund phrases (e.g., “pressurizing a chamber” or “sending a transmission”).

Alternatively, software-implemented inventions may utilize computer-readable medium (CRM) claims. These are usually thought of as an object (like a system claim) that is programmed to perform a series of steps (like a method claim) — making them a hybrid type of claim.

Independent vs. Dependent Claims

Another way to categorize claims is independent claims versus dependent claims. As the names suggest, each independent claim stands on its own, whereas dependent claims always refer back to (and “depend” from) another claim.

| Independent claims | Dependent claims | |

| Scope | Broadest claims in the patent | Further narrows the scope of an earlier, independent claim |

| Identifying features | Typically start with the word “A” (like “A system …” or “A method …”). Don’t refer back to another claim. | Always explicitly refer to another claim (like “the method of claim 3…”). |

| Should it be used to determine if a product or process infringes the patent? | Yes. | No. At least not primarily. |

| Why? | If the product infringes even one of the independent claims, then the product infringes the patent. If the product does NOT infringe any of the independent claims, the product doesn’t infringe the patent. | Dependent claims are always narrower than the claim that they depend from, meaning that a product CANNOT infringe a dependent claim unless the product also infringes the claim from which it depends. But dependent claims are useful for interpreting the independent claims, so don’t ignore them. |

Even though dependent claims can’t be used to determine if a competing product or process has infringed the patent, they’re still important because they provide a backup position for enforcing the patent. For example, even if one of the broader claims is found to be invalid, the dependent claim may still be valid.

How Can We Analyze a Patent’s Claims More Thoroughly?

Interpreting the claims in a patent can be a complex and rigorous process. If you’re looking to do a more nuanced analysis of a patent than what’s covered in this overview, we recommend consulting a qualified patent professional instead.

At Henry Patent Law Firm, our attorneys have successfully prosecuted a diverse range of patent filings — so if you have additional questions about how to further evaluate a patent, don’t hesitate to contact us.

Michael K. Henry, Ph.D.

Michael K. Henry, Ph.D., is a principal and the firm’s founding member. He specializes in creating comprehensive, growth-oriented IP strategies for early-stage tech companies.