There’s often confusion about the purpose and impact of adding more claims in a patent application, and inventors often wonder whether the number of claims will affect the overall strength and value of the patent.

The claims are the most important part of a patent because they determine what’s actually covered by the patent. But does that mean that more claims are always better?

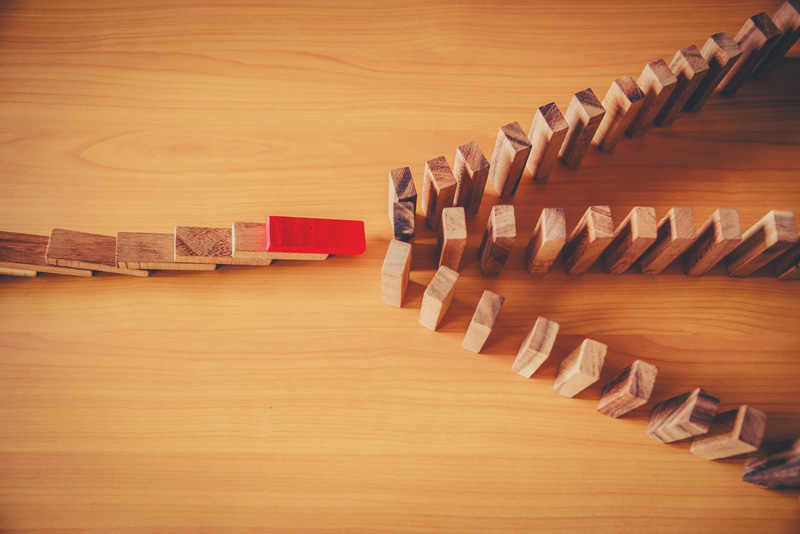

Generally speaking, yes – a patent with more claims is more likely to withstand challenges in an adversarial setting. As a patent litigator used to tell me, patent claims in litigation are like soldiers in a battle: many will not survive. And because patent applications are typically drafted years before litigation begins, you simply can’t predict every single challenge you might face when you’re drafting a claim set.

But in patent litigation, you generally need only one claim to survive. As such, the key to a successful patent application lies in having enough claims so that at least one or two can survive all the challenges that the patent will eventually face in a litigation context.

As a practical matter, more claims translate to higher cost in the drafting and filing process. And the patent office will often require you to cancel claims if you have too many. So, you have to draw the line somewhere. But where?

The Unpredictability of Patent Challenges

Challenges to patent claims typically fall into one of three broad categories: 1) prior art, 2) subject matter eligibility, and 3) clarity or support.

But as we’ll explain below, the specific nature of each challenge is always a bit of a moving target, which is why you need multiple claims to account for uncertainty and unpredictable events.

Patent Claim Challenge #1: Prior Art

Prior art refers to any evidence that your invention was already publicly known or available, in whole or in part, before the effective filing date of your patent application. In litigation, a third party may use prior art to show that your claimed invention is not “novel” or “non-obvious.”

It’s impossible for you to know all of the relevant prior art before you file a patent application, or even after the patent has been issued:

- Some patent applications that qualify as prior art may not be public yet due to the 18-month publication window

- Not all prior art will show up in a typical search

In other words, a motivated infringer who’s willing to conduct an extensive (and expensive) prior art search can often find an obscure reference that can be used to challenge the validity of your claims.

For this reason, you need to have enough claims in your application to ensure that unexpected prior art won’t invalidate your entire patent. To take a deeper dive into how this works, check out our blog post discussing what happens if you discover prior art against an existing patent’s claims.

To hedge against uncertainty relating to prior art: Consider drafting many detailed dependent claims. Too often — especially when a patent application is drafted on a tight budget — patent attorneys draft only short, broad dependent claims that simply recite conventional elements.

While those types of dependent claims can certainly have some value, it’s also important to have at least a few narrow dependent claims that focus on how the novel elements of the invention work and how they’re implemented. These types of claims can be critical in navigating unexpected prior art.

Patent Claim Challenge #2: Subject Matter Eligibility

An invention is only patent-eligible if it covers a “process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter,” and doesn’t fall within any of the judicial exceptions: laws of nature, abstract ideas, and natural phenomena.

That may sound straightforward enough, but in fact, subject matter eligibility has turned out to be one of the least predictable areas of the U.S. patent system over the last decade. In particular, landmark SCOTUS decisions like Alice and Mayo have resulted in significant confusion around what constitutes an “abstract idea” (which is not patentable).

Besides, the law of subject matter eligibility (“Section 101”) is very likely to change again. For example, there have been many bi-partisan legislative attempts to rewrite Section 101 in recent years, and future attempts could certainly gather enough momentum to pass into law. Even if new legislation doesn’t pass in Congress, the contours of subject matter eligibility continue to evolve as new case law emerges over time.

Because of all these uncertainties surrounding subject matter eligibility, you must have some claims to account for variability in the way that Section 101 will be applied by a judicial body. The main risk is that your broad independent claims will be construed as an “abstract idea” that is not patent-eligible.

To hedge against uncertainty in subject matter eligibility: Consider drafting (in addition to broad independent claims) one or more narrower independent claims that describe a concrete application of the invention or a specific embodiment of the invention.

Patent Claim Challenge #3: Clarify

In recent years, it’s also become harder to enforce a patent that uses vague claim language. This is because it’s become easier for someone challenging a patent to show that patent claim language is “indefinite” and therefore invalid.

Moreover, the meaning of many words can change over time and can be subject to multiple interpretations. Since litigation usually takes place many years after the application is filed, there’s always a degree of uncertainty surrounding how your claims will be understood when your patent eventually needs to be enforced.

You can account for these uncertainties by having multiple different claims with different types of wording: If one of them is unclear, perhaps the other will survive.

To hedge against uncertainty with regard to the clarity of claim language: Consider drafting two independent claims that cover the same invention but use different terminology for certain key features.

For example, one of your independent device claims might use a “means plus function” limitation while the other does not. Or one of your independent system claims might use a broad term of art to refer to a certain component, while another independent system claim explicitly recites the key features of the component (without using the term of art).

Why Having Lots of Claims Matters: LG v. Mondis Case Study

There are several cases that illustrate why having lots of claims can prove advantageous during litigation. Take, for example, the case of LG v. Mondis.

What Happened in LG v. Mondis?

In 2014, Mondis Technology Ltd. filed a lawsuit against LG Electronics, claiming that LG was infringing claims of their patent for plug-and-play technology (U.S. Patent No. 7,475,180). LG responded by filing an inter partes review (IPR) challenge against the asserted patent.

During the IPR process, most of Mondis’s claims were overturned; just three of the 29 claims survived. But that was enough for Mondis to proceed with its infringement case.

In April 2019, a jury found that LG had willfully infringed only two of the three surviving claims of the patent, and awarded Mondis $45 million in damages.

Why It Pays to Have Lots of Claims

Mondis couldn’t have known beforehand that those two specific claims would eventually be the ones to survive reexamination and ultimately be worth tens of millions of dollars.

Given the number of claims that were invalidated, had the patent contained just one or two independent claims, it’s very likely that Mondis would not have succeeded in its infringement action.

And there’s nothing special about this particular case — it’s just one example that demonstrates the general rule: the majority of your patent claims will not survive all the challenges of patent litigation, and having a large number of claims increases your chances of having at least one valuable claim survive.

Best Practices for Drafting Multiple Claims

By drafting a matrix of claims with diverse language and scope, you can help ensure that some claims will survive even if others fall — ensuring that anyone who tries to use your technology will end up navigating a legal minefield instead.

To achieve this, your patent application should include:

- A mixture of broad claims, narrow claims, as well as varying levels of breadth in between. This makes it harder for an opponent to invalidate your entire patent at once.

- Multiple claims that use different language to describe a similar scope. That way, if one phrasing is unclear, you have claims with a different phrasing that might still survive.

- Method, system, and apparatus claims. Different claim groups may define your invention differently, and so may be applicable in different types of situations.

In addition, you’ll want to draft as many claims as possible upfront, before you file your application. This will provide support for additional claims in the event that you need to file continuations in future (because you can’t add new matter to a continuation). To that end, your initial filing should describe all the different claims that might be valuable.

So How Many Claims Should I Draft in My Patent Application?

While we generally advocate for crafting lots of diverse claims in your patent applications, the specific number of claims will ultimately depend on the invention you’re patenting and your available resources. For advice on your specific situation, please contact a qualified patent professional.

At Henry Patent Law Firm, we’re always eager to hear from leading tech innovators. Contact us now to find out how we can help!

MINIMIZE THE RISK THAT YOU’LL ENCOUNTER UNEXPECTED PRIOR ART. HERE’S WHAT SMART TECH COMPANIES NEED TO KNOW.

But what should you do if you discover prior art against your invention? Download our FREE eBook to find out. Learn the following:

- How does the industry define prior art?

- How can you do an effective prior art search — and can you do it yourself?

- How will discovering prior art affect the claims in your patent application?

- What steps can you take to avoid unexpected prior art?

- How can you avoid accidentally creating prior art against your own patents and applications?

Walk away equipped with smart strategies to navigate common prior art obstacles during the patent process.

Fill out the short form on this page to download this eBook today!

GET YOUR FREE EBOOK

Michael K. Henry, Ph.D.

Michael K. Henry, Ph.D., is a principal and the firm’s founding member. He specializes in creating comprehensive, growth-oriented IP strategies for early-stage tech companies.